LACMA Unframed: Yoshitomo Nara: A Conversation with Curator Mika Yoshitake

March 10, 2021

Arthur Nguyen

Read hereYoshitomo Nara: A Conversation with Curator Mika Yoshitake

By: Arthur Nguyen

When LACMA temporarily closed to the public in March 2020, Yoshitomo Nara’s highly anticipated retrospective at the museum was in the midst of being installed. I spoke with exhibition curator Mika Yoshitake about installing this vast and intricate exhibition during the pandemic, and its significance in a time of great uncertainty and deep reflection.

What makes the Nara retrospective at LACMA stand out from other Nara exhibitions you’ve seen or worked on?

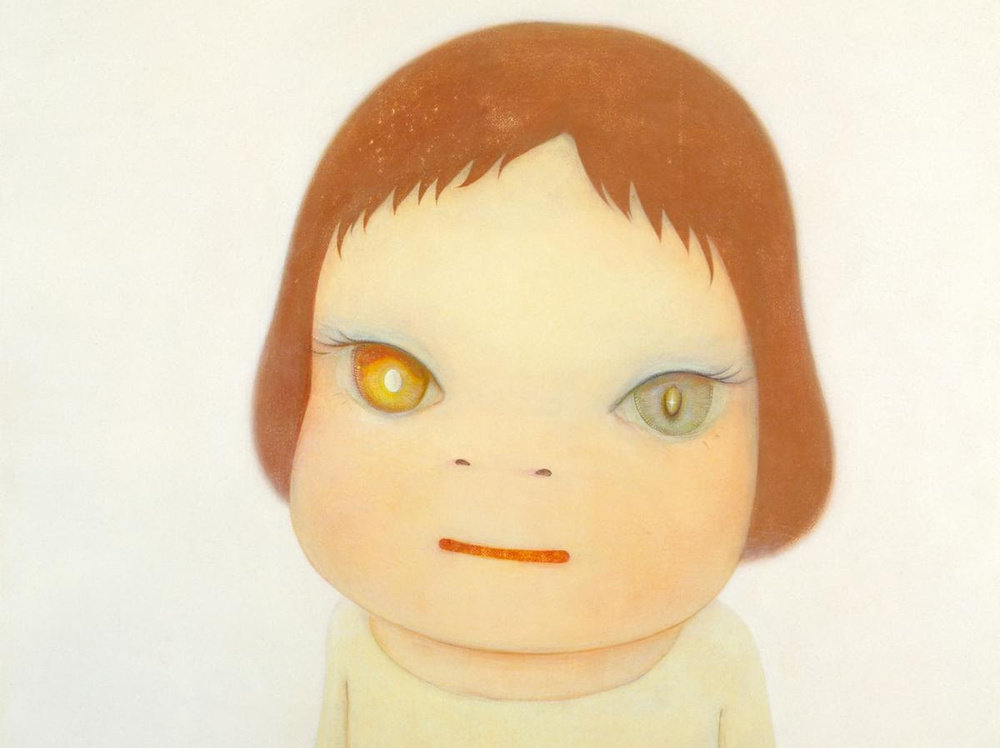

LACMA’s Nara retrospective stands out from the artist’s previous surveys in that it is the most expansive of his career, in both scale and scope, spanning over 36 years of the artist’s practice with more than 100 major paintings, ceramics, sculptures, and installations, as well as 700 of his most intimate works on paper. It also includes over 350 vinyl records from his personal collection. The show follows the evolution of Nara’s career as he has unwaveringly probed the visceral power for self-reflection and healing, which has now become even more relevant in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and global uprisings. Particularly over the last 20 years, Nara’s work has become increasingly contemplative, while simultaneously maintaining allegorical, introspective, and confrontational elements. This exhibition is an opportunity to witness how he accesses the emotional psyche of each generation—the equivalent of this is the affective power of music.

While I was living in Japan from 2007 to 2011, I was amazed to witness how Nara honed and developed the layers of tonal saturation that create prismatic effects in his portraits. After the devastating 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami (the epicenter was just 43 miles northeast of his studio), he was unable to paint for nearly a year. Instead, Nara immersed himself in the world of Shigaraki ceramics, and also made monumental bronze portraits at a Buddhist foundry, confronting the complexity of his feelings through the physicality of these materials. The result was a group of dark, meditative heads, large and oblong; to me these resonate like death masks for the spirits of lost lives.

Viewers at LACMA will experience a selection of Nara’s favorite ceramic vases and figural sculptures, such as Little Thinker in the Garden, as well as a 26-foot version of Miss Forest, a white urethane paint-on-bronze sculpture gracing Wilshire Boulevard. There is a fragile imprint of the artist’s finger pressed against the closed eyelid of Miss Forest, whose head rises into a tall evergreen tree in honor of Nara’s roots in northern Japan. To me, a healing power resonates in this work, making it a cornerstone of this exhibition.

Why is it an important show to see, both for Nara devotees and for newcomers to his work?

I think that Nara is perhaps one of the most misunderstood artists of his generation. Recent articles by scholars have tried to denigrate his popular appeal as pandering to masses of “girl fans” in a way that is problematically gendered and elitist. But Nara’s works reveal challenging and, at times, controversial narratives underneath the popular and cult-like status of his portraits.

The ability to showcase the full scope of his practice within the context of Los Angeles is also critical, because Nara has deep roots in L.A.: Paul McCarthy (who had met Nara in Tokyo) invited him to teach for a semester at UCLA in 1998, along with Takashi Murakami. Nara lived in Germany in 1988–2000, so it was in L.A. that Nara really spent time with Murakami; the two even shared an apartment that semester.

Contrary to popular belief, Nara did not rise out of the Japanese “Neo-Pop” context of Murakami and others (known for appropriating Japanese consumer culture, anime, and manga). During his years in Germany and extensive travels through Europe and other parts of the world, Nara’s aesthetic was built from very personal encounters with music and art: international subcultures of rock, punk, and folk music; flea market figurines and Baroque devotional figures; Buddhist sculptures from the Kamakura period; early Renaissance and British landscape paintings; 1980s German iconoclasm by artists like A.R. Penck and Fritz Schwegler (Penck was his professor at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf); as well as modern and wartime Japanese painting and 1960s Japanese underground experimental comics.

While many of Nara’s portraits appear “cute” (kawaii) on the surface, upon closer viewing, a singular portrait can exhibit a complex range of expressions including grief, rage, pain, and affection, which alternate the longer you stare at the image. And his handling of paint is certainly not “superflat.” My hope for this show is to give Nara devotees a chance to see the amazing breadth of his work and newcomers a more complex and nuanced view of an artist who is so often miscategorized.

Music is a primary source of inspiration for the artist. How does that aspect of his work translate into the physical space of the exhibition?

Music’s affective power and Nara’s love of American and British folk rock infiltrates every part of this exhibition. Moving through the show, one can pick up on certain cues in the images: visual motifs, riffing on lyrics, and album titles. Many works feature song lyrics that dramatize the emotional content of the work, and one’s knowledge of the songs creates a deeper understanding. In Make the Road, Follow the Road (1990), “Nothing ever happens, nothing,” billows from a ball of fire in a girl’s hand, invoking the lyrics of Scottish rock band Del Amitri’s 1989 song “Nothing Ever Happens.”

Others involve humorous “translations” from album art to painting. For example, Nara adopts the pose of a man photographed lying down on a sofa with his leg raised on the album cover of Donnie Fritts’s One Foot in the Groove (2008) for his 2010 billboard-size painting of the same title, which features a girl in the same pose on a cloud. Some works draw on the mood of an album, such as Richard and Linda Thompson’s I WANT TO SEE THE BRIGHT LIGHTS TONIGHT (1974). The album cover’s yellow-green palette with fiery red title letters spelled out on wet glass translates into Nara’s serene 2017 wide-eyed portrait, which clearly nods to the album with the same title. Finally, recorded music from the artist’s playlist (accessible via LACMA’s website) can be heard in My Drawing Room (2008), a recreation of the artist’s drawing studio.

Nara encourages viewers who get his music references to hum along to the songs as they look at the works. This is also what inspired the production of a deluxe-edition catalogue with a vinyl record to accompany the exhibition.

What was the installation process like? How was it affected by the pandemic?

The installation process was incredibly challenging. We started installing the show as the country was just coming to terms with the pandemic in March. The rapidly changing understanding of the pandemic’s scope meant I had to be responsive to both the artist’s and LACMA’s concerns.

When coronavirus cases were first largely being reported in Asia in February, we encouraged Nara to try to install the show remotely via FaceTime from his studio in Japan. This proved to be unfeasible, especially with the salon-style hang of over 400 framed drawings. After sending him a sample elevation floorplan with thumbnails that he could work with digitally, Nara responded, “I am very analogue. My brain does not work this way.” In the same way that he works alone in his studio with no assistants and maintains full control over every step of his production process, Nara needed to physically sense the scale and space of the galleries in order to install his work. If he did not have a chance to oversee the installation of his first international retrospective, he said he would regret it for the rest of his life.

Nara arrived on LACMA’s campus on March 16, right when the pandemic began rapidly escalating in the U.S. The museum soon suspended all work in galleries, so we stopped just two days later on March 18. With all hands on deck and a race against time, Nara made rapid-fire decisions and together with the incredibly perceptive installation crew, we installed over half of the exhibition in just three days. This experience has been a critical lesson in clear communication and translation—not only communicating in different languages, but also mediating cultural translation, and prioritizing the health and safety of everyone involved.

Fortunately, many of the lenders have generously agreed to extend their loans through July 5, 2021 at LACMA and we are currently reworking the new dates for the international tour.

Memory, nostalgia, and other deeply felt emotions also infuse Nara’s work, and we are living through a time when all of us are forming intense new memories. How do you think the emotionality of Nara’s work will resonate with audiences in our new reality?

While we have had to suddenly adapt to new circumstances, this period has also allowed us to pause and have a heightened sense of self-awareness. The emotionality of Nara’s work—especially in the complexities imbued in portraits like Midnight Truth (2017), with piercing eyes that stare into the depths of one’s interior—has resonated with the adjustments I’ve experienced in my own life: abruptly having to let go of the fluidity of travel, struggling to balance work and homeschooling my four-year-old, and reconnecting with the people closest to me as we all face an uncertain future. I believe Nara’s work has the power to confront, heal, and deepen our sense of self.

In addition to his practice, Nara has traveled to engage with Indigenous communities in Sakhalin, organized an annual residency educating children in rural Hokkaido, and visited war-torn Afghanistan and refugee families in Jordan. Through these and other life experiences, he has built a political consciousness for peace. This is reflected in works like No Nukes (1998), an early representation of Nara’s strong stance against nuclear weapons, which is now synonymous with the anti-nuclear protest movement. In July 2012, it became a powerful symbol when the artist allowed protesters to download the work to use as picket signs during one of Japan’s largest anti-nuclear protests. As many as one hundred thousand people gathered to protest the government’s decision to restart two nuclear reactors in Fukui prefecture, many with “No Nukes Girl” in hand.

Regardless of language, age, race, culture, or background, I believe Nara’s art has an unusual power to not only reach a mass audience, but also evaluate the meaning of human co-existence.